DOWNLOAD COMPUTERIZED PATIENT TEST DATA AND PHOTOS

Abnormal head and neck posture can affect jaw posture, which can contribute to a TMD condition. A forward head posture or tilted head can result in pressures within the neck vertebrae resulting in nerve pressure and muscle fatigue. All of these structures are interconnected with the relationship between the jaw and skull, its nerve supply and muscle system and the way the teeth fit together. Other body postural asymmetry in the shoulders, hips and back can also adversely affect head, neck and jaw posture and should be appraised.

Light finger palpation, when applied to a muscle should not cause tenderness or pain. If palpation elicits a verbal or visual response, it is an indication of the presence of inflammation, hyperactivity or spasm in a muscle. Posterior and lateral cervical muscles as well as the upper quadrant muscles area also palpated as dysfunction as these muscles can affect the masticatory muscles in a collaborative manner.

The doctor gently palpates the muscles responsible for the movements of the jaw on the sides of the temples (temporalis) and the sides of the cheeks (masseter). The masseters are pressed between fingers outside and inside the mouth. Both of these muscles close the mouth. The masseter is activated when the teeth come into occlusion. Below the jaw palpate the group of muscles including the digastric, which open the mouth. The angle of the mandible, which is often tender in TMD patients is also palpated. It includes muscles and ligaments intimately associated with mandibular movement. In a differential diagnosis, the parotid gland must be considered as it traverses this area as well.

Since TMD can co-exist with cervical musculoskeletal dysfunction, the muscles on the front, sides and rear of the neck and the shoulders are often tender. They act upon the cervical spine and collaboratively with the mandibular muscles as head and cervical posture directly affect mandibular posture. Disorders within the muscles and nerves in the neck can also cause the sensation of pain referred elsewhere in the body confusing the diagnostic and treatment process. Head and neck posture as well as whole body posture should be appraised with the patient standing.

Three very significant structures should be palpated on each side. In the upper rear of the mouth behind and above the last maxillary molars are the external or lateral pterygoid muscles responsible for lateral (side) movement of the mandible as well as opening of the mouth. Adjacent to the lateral pterygoid muscles is another muscle, the tensor veli palatini, which open the eustachian tube connecting the middle ear and the rear of the throat called the eustachian tube. The eustachian tube equalizes pressure in the ear with outside air pressure. TMD patients may experience spasm of the lateral pterygoid muscle and also of the adjacent tensor veli palatini, which fails to open the eustachian tube. Patients may experience muffling of sounds or ear pain due to the failure of the eustachian tube to open properly and ventilate the middle ear.

Three very significant structures should be palpated on each side. In the upper rear of the mouth behind and above the last maxillary molars are the external or lateral pterygoid muscles responsible for lateral (side) movement of the mandible as well as opening of the mouth. Adjacent to the lateral pterygoid muscles is another muscle, the tensor veli palatini, which open the eustachian tube connecting the middle ear and the rear of the throat called the eustachian tube. The eustachian tube equalizes pressure in the ear with outside air pressure. TMD patients may experience spasm of the lateral pterygoid muscle and also of the adjacent tensor veli palatini, which fails to open the eustachian tube. Patients may experience muffling of sounds or ear pain due to the failure of the eustachian tube to open properly and ventilate the middle ear.

In the lower rear of the mouth, located on the inner aspect of the angle of the mandible are the internal or medial pterygoid muscles. The medial pterygoid muscles are part of the system that includes temporalis muscle that closes the mouth. Posterior to the mandibular occlusal plane is the attachment of the tendon of the temporalis muscle along the anterior edge of the ramus. When the anterior temporalis muscle is found to be tender during the extraoral examination, its tendon is likely to be reported to be tender intraorally. This is a corroborative finding. The masseter muscle examination described earlier involves using the thumb on the inner aspect of the muscle as it is palpated from its attachment inside the zygoma down to the angle of the mandible.

The amount of vertical overbite and horizontal overjet of the anterior teeth is measured and recorded. Excessively deep overbite is often found in patients with TMD (Figure #1). It is commonly associated with overclosure of the jaw and associated mandibular distilization with pressure in the TMJ joint, possible disc displacements and muscular fatigue all of which can be present in a patient with TMD.

The amount of vertical overbite and horizontal overjet of the anterior teeth is measured and recorded. Excessively deep overbite is often found in patients with TMD (Figure #1). It is commonly associated with overclosure of the jaw and associated mandibular distilization with pressure in the TMJ joint, possible disc displacements and muscular fatigue all of which can be present in a patient with TMD.

This phenomenon was initially described by James B. Costen, MD an otolaryngologist in 1934. Acknowledging his contribution, TMJ disorders were historically referred to as Costen's Syndrome. "A syndrome of ear and sinus symptoms dependent upon disturbed function of the temporomandibular joint. Ann Otol Rhinil Laryngol 1934: 43(1):1-15

The incisal edges of the anterior teeth that are normally smooth with rounded on the corners. If they are worn flat, sometimes showing a labial facet and possibly a brown stain, it is a sign of a longstanding abnormal bruxing habit with a loss of enamel. This is often seen in TMD patients (Figures #2 and #3). It can also be the result of muscle function as an attempt to "free" the mandible from posterior displacement resulting from the dental occlusion.

The doctor measures the maximum interincisal space between the upper and lower incisors (physiological range is 35-50 mm). Abnormalities are indicated by reduced capacity to open, opening with pain in the muscles or TMJ joints, and opening towards one side rather than straight down. The doctor also observes the quality of opening as to whether it is fluid or staggered and strained and measures maximum opening and bilateral excursive jaw movements as range of motion.

The TMJs are bilaterally palpated anterior to the tragus of the ear before opening, with the mouth open wide and closed. Pain or tenderness over the joint is an indication of an inflammation in the joint capsule or within the joints. The mandibular condyle normally rotates and translates forward as the mouth is opened. If the condyle cannot move forward and downward along the slope of the joint fossa as the patient opens wide, it indicates that either muscles or something intracapsular, within the joint is obstructing or preventing the forward condylar translation. A click may be felt beneath the doctor’s fingers. That too indicates an abnormal state.

The TMJ can also be palpated posteriorly by application of gentle finger pressure forward on the front wall of the outer ear canal. The forward wall of the ear canal is actually the rear wall of the TMJ. In the absence of any ear disease, pain on palpation is an indication of inflammation in the retrodiscal tissues of the TMJ. Palpation of the condyles upon complete closure of the teeth indicates posterior displacement of the condyle, as observed by Dr. Costen decades ago.

The doctor listens to the TMJ with a stethoscope as the patient opens, closes and moves the jaw from side to side. Sound in the joints is abnormal. The type of sound, whether a distinct click or a crackling sound is significant as each represents a different state of joint dysfunction. The position in the open/close cycle at which sound is heard is also important. Many people have sounds in their TMJ and no other symptoms and may not require treatment.

Notably all of these clinical examination procedures provide diagnostic impressions enabling the examining physician or dentist to make an initial diagnosis. The computerized instrumentation, which the dentist is able to use after this clinical examination, provides hard data, actual precise measurements of these same functions; jaw movement, muscle function, TMJ function and joint sounds before and throughout treatment.

Often, a virtually imperceptible (invisible) misalignment of the jaws with upper and lower teeth meeting in the wrong place can be at the root of TMDs. This misalignment can prevent the jaws from meeting in a position, which maintains muscular relaxation and health as nature intended, requiring the muscles to function in an uncomfortable manner. The misalignment may look like a typical dental malocclusion or may look like a beautiful occlusion of the teeth. By visually observing, feeling and listening alone, doctors cannot totally observe and evaluate the presence of subtle dysfunction. To trace and identify this malocclusion, or “unhealthy bite,” and to measure the associated muscle function requires a revolutionary set of computerized instruments developed over the past forty years.

The CMS is a tracking device that records, in three dimensions, the delicate functioning movements of the jaw with accuracy in tenths of a millimeter. Recordings are made of the movement of a small magnet temporarily attached to the gum below the lower front teeth. Opening, closing, swallowing and chewing movements can be scrutinized and analyzed. The natural occlusion and the healthy neuromuscular occlusion treatment positions can be located with this computerized instrument. This testing is used at the initiation of treatment and thereafter to evaluate the accuracy of jaw position at the treatment occlusion.

This instrument measures and analyzes the electrical activity in the muscles that move the jaw at rest and during function. In health, muscles rest with low levels of electrical activity and function with high levels of balanced activity. In TMD the reverse is often observed. Illustrative data demonstrate the resting EMG activity before and after TENS (electrical stimulation therapy to relax muscles) as well as the Functioning (clench) EMG activity in the natural bite and in the corrected neuromuscular occlusion used for treatment. EMG is a painless test, which is performed using surface electrodes placed bilaterally, on the anterior temporalis, masseter and digastric muscles. The device demonstrated in the graphics below can also monitor a fourth pair of muscles selected by the dentist. Resting electrical activity as well as maximum voluntary clenching, representing the two ends of the spectrum of muscle function can be tested with EMG.

Graph 1

Graph 2

Graph 3

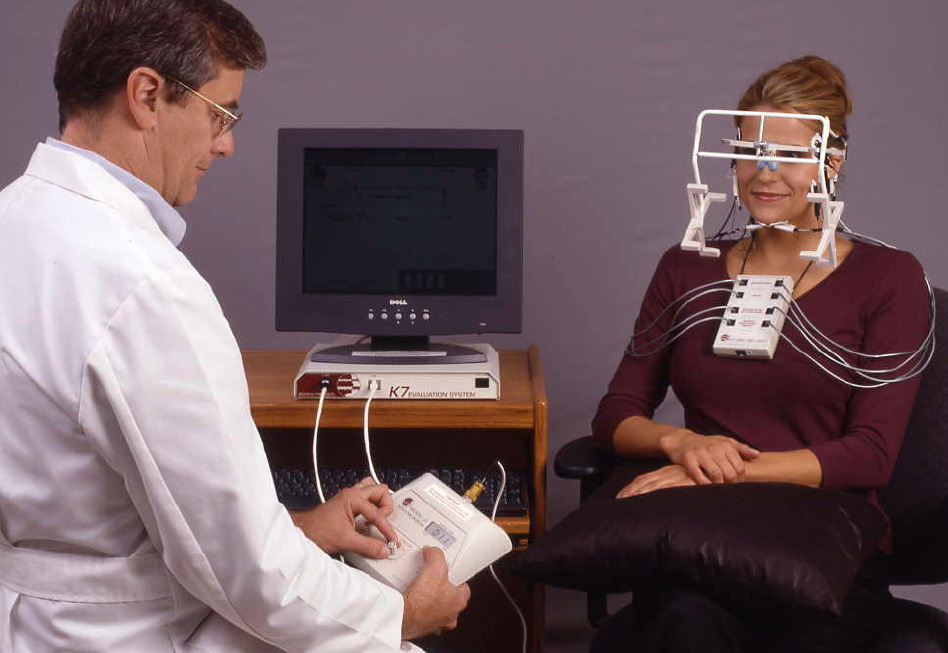

Recordings of sounds produced within the jaw joint (TMJ) can be recorded and analyzed during opening and closing of the mouth more sensitively, precisely and reproducibly than by the traditional technique of listening with a stethoscope. ESG records the frequency and amplitude (power) of the noise produced, as well as the position in the opening/closing at which sound is produced. This enables the dentist to evaluate whether there is damage within the TMJ and suggests its nature for which further study may be necessary. The test is performed by placement of a headpiece similar to that of a headset with vibration sensors (transducers) over the two temporomandibular joints (TMJ).

Recordings of sounds produced within the jaw joint (TMJ) can be recorded and analyzed during opening and closing of the mouth more sensitively, precisely and reproducibly than by the traditional technique of listening with a stethoscope. ESG records the frequency and amplitude (power) of the noise produced, as well as the position in the opening/closing at which sound is produced. This enables the dentist to evaluate whether there is damage within the TMJ and suggests its nature for which further study may be necessary. The test is performed by placement of a headpiece similar to that of a headset with vibration sensors (transducers) over the two temporomandibular joints (TMJ).

The treating dentist determines what type of imaging is necessary for each patient and at what point in the diagnosis or treatment it is necessary to obtain information from imaging. TMJ imaging includes various types of views such as lateral trans-cranial, panoramic, frontal, CT scans, and MRI when medically necessary to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of a patient.

The actual diagnosis is made by the TMD-trained dentist, who accumulates, analyzes and assimilates all of the information obtained from the patient’s history, clinical examination and various diagnostic tests described above. The computerized testing, which provides valuable information, does not make a diagnosis by itself. It is the trained doctor, who assesses all the data obtained, makes the diagnosis and determines the appropriate treatment plan for that patient. Actual treatment frequently involves the temporary creation of a new therapeutic biting position. This neuromuscular occlusion position incorporates healthy muscle function and proper interdigitation of the teeth to create a healthy, comfortable bite.